Exhibition: First Light, Galerie Tschudi

Unnatural History

Between 1946 and 1958, at a remote Pacific Atoll, 23 of the most powerful manmade explosions in history occurred. During this period, bombs delivering a combined fission yield of 42.2 megatons were detonated. The force of one of these, ‘Castle Bravo’, was enough to vaporize two islands, and gouge a massive crater – measuring 2000 metres in diameter – out of the primordial reef. Another, codenamed ‘Baker’, threw a fleet of 70 captured and decommissioned WW2 battleships – some of them up to 250 metres long – up into the air. A few were ripped to shreds. Others, like the USS Saratoga and the HIJMS Nagato – storied flagships of the US and Japanese navies – eventually sank to the bottom, where their rusting hulks remain today. During this period, obliterated geology would become radioctive particles, carried on the wind to then fall on communities in neighbouring atolls. Meanwhile, the people of Bikini, who had been ‘asked’ to temporarily leave their home to make way for a series of experiments ventured ‘for the good of mankind and to end all wars’ began to learn the meaning of an exile and dispossession that continues until present. Today, the atoll’s islands bear architectural scars that stand as profane registers of this program and its unresolved consequences; a series of concrete bunkers, jutting out from the shore or hidden beneath jungle.

First Light is a new body of work exploring fraught interactions between industrial modernity and geography – addressing the atomic landscape and post-colonial ecology of Bikini Atoll. The works in this exhibition issue from Charrière’s month-long expedition to its radioactive and abandoned sites. Partially inspired by science fiction author J.G Ballard’s The Terminal Beach (1964), they picture terrain above and below water – from palm-fringed beaches to the rusting Pacific ‘Ghost Fleet’, submerged some 180 feet below sea level. The project follows a previous series of works created at the Soviet ‘Semipalatinsk’ nuclear test site (Kazakhstan, 2014), recording the architectural legacy of the birth of the atomic age. As such, First Light is the second part of an exhibition diptych exploring 20th Century nuclear landscapes on both sides of the Iron Curtain.

Settled by humans for approximately 3600 years, prior to atomic exodus, the 20th century history of Bikini stands as a signal example of modern techno-colonial hubris. Its English name is transliterated from the Marshallese, Pikinni (pji͡ɯɡɯ͡ injːii̯) – ‘Pik’ meaning ‘surface’ and ‘Ni’ meaning ‘coconut’; surface of coconuts. The biological fate of the island’s namesake flora, as well as the currency that the word ‘Bikini’ possesses today, are symptomatic of a profound historical ungrounding that has cut across socio-linguistic, civil and biological fields: Following the test program, all of the coconut trees on Bikini were utterly irradiated and had to be cut down. Eventually, the island’s bare surface was replanted in a grid formation – a suitably unnatural, ‘rational’/modernist geometric overly. Thirty years later these new trees would also prove contaminated, when tests on repatriated Bikinians recorded immense levels of cesium uptake due to consumption of their traditional dietary staple. Because of these findings resettlement had to be abandoned. When one visits Bikini today some trees register a pronounced genetic mutation – their nuts long and thin, the shape of marrows, or missiles, too narrow to produce milk or flesh. Setting these misshapen samples in a series of vitrines that recall an ethnographic museum display, Charrière foregrounds the colonial ‘sculpting’ of the region’s biosphere by foreign radioactive technologies. This series, titled Lost at Sea - Pikini-Fragment, proffers a post-apocalyptic botanical survey; an ‘unnatural history’. Standing vertically on a bed of coral sand, inside a glass housing that caps a mirror-sided plinth, each coconut might be interpreted as a castaway that has been washed up on another identificatory shore. In this arrangement the sand implies a kind of terminal beach, while the mirror – long symbolic of water, and vanity – draws the viewer into its image-space. The fact that these coconuts stand erect, like totemic phalluses – suggestive of potency – is a bitter irony: Coconuts of this sort are utterly sterile from a reproductive standpoint. That the Marshallese creation myth involves a paradigmatic mother giving birth to a coconut, which then supplies her people with sustenance, tools and clothing, sets the profound degree of this and other genetic disruptions into relief.

On the international cultural plane, Bikini’s ungrounding plays out in its hegemonic linguistic identification. MS Word’s autocorrect allows ‘Bikini’ but not ‘Bikinian’. Rather than a place, a culture, or a people, the designation has – as we all know – become associated with something different. French designer Louis Réard named his women’s two-piece swimsuit after the atoll in 1946, trading on ‘explosive’ media associations. The item’s ubiquity now firmly established, its association with sun, sex and leisure has completely succeeded its namesake almost everywhere except the Marshall Islands. Charrière’s series of large-format photographic prints oftypically idyllic island scenes conjures Bikini’s sublimated trauma. Depicting water, palms, beaches and horizons, sand from nuclear ‘hot’ sites has been placed on the photo negatives during their development process, altering the images in an arresting fashion. These prints oscillate between the peaceful cliché of tropical sunset photography and the destructive beauty issuing from atomic ‘second suns’. In them the manmade energy of the landscape undermines, literally, the image of paradise typically found in tourist brochures. Exposing the film stock to radioactive material destroys one mode of (photographic) visual information, while at the same time adding another. The result is a doubly synthetic topography.

In another group of photographs Charrière employs the same atomic development process to catalogue the atoll’s architectural development under the nuclear program; depicting bunkers built for command, control and observation of the tests. Like his Kazakh series, these black and white works recall the objective style of the Duesseldorf school while surveying the apotheosis of mid- century atomic-industrial architecture. With their rusting iron rebar and crumbling concrete, now falling like flakes – prey to salt air and, once, unimaginable vibrations – some of these structures recall pyramids; odious leftovers of a questionable ideal.

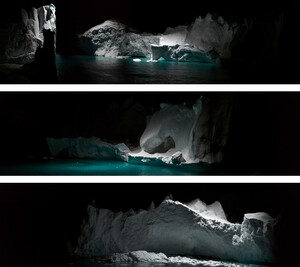

Developing this approach, Charrière’s new video work – entitled Iroojrilik – captures these structures’ decay, its manner of editing further suggesting morphological overlaps with the monstrous wrecks lying on the bottom of the Bikini Atoll lagoon, assailed by tide and time. Making no use of archival material – its original underwater images captured at depths far below standard dive profiles – Iroojrilik is unquestionably the most unique, and comprehensive, perspective on the maritime ruins of Bikini ever put together. Yet, rather than explicating individual vessels or buildings, the cumulative impression given is that of an Atlantis or lost civilization – architectural features of one ship cut together with those of others, such that it appears as though a submerged mega-structure has been discovered. On a more general note, the film employs another series of elisions and substitutions. Through a series of montages, mixing sunsets and sunrises, it proposes an uncertain distinction between daybreak and nightfall – first light of a new day in Pacific history, and the waning of another: Visions of multiple suns and endless dawns stretch across the the horizon. Pictorial energies shift and sway, like palm trees and coral ferns growing on cannon mounts, between construction and destruction; transporting the viewer to a ‘non-place’, or the beginning of a brave new world. Like other works in the exhibition, Iroojrilik is a sensitive meditation on beauty, atrocity, and memory.

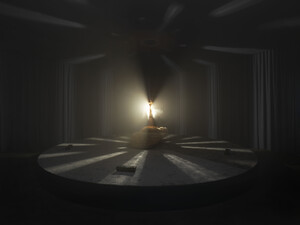

In addition to the aforementioned works, paying tribute to the people of the Marshall Islands, their historical suffering, and the irreparable damage done to their landscape, Charrière’s proposes Pacific Fiction - Study for Monument – a sculpture that serves as a putative model for future memorial. The work incorporates a pile of coconuts encased in lead. The piece symbolizes the traumatic embrace of this region by the atomic project; the lead coating suggestive of smothering – registering a profound colonial imposition. In addition to this, the sculpture reflects upon safety and hope: In physical terms, lead ‘contains’ the danger posed by the radiation present within the coconuts. The pyramid form, further, recalls a stockpile of cannonballs – this ‘fruit’ of atomic knowledge standing ready for deployment, for good or ill. But it also invokes a tomb, like the pyramids of Egypt, the deathly architecture of the bunkers on the shores of Bikini’s Atoll, or the angular iron monoliths sleeping in the deep.

Like a shockwave, moving across the ocean to break upon foreign shores, modern history is the story of developments elsewhere effecting those close to home. Whether or not the US government will deliver the full reparations once promised to the people of the Marshall Islands, and whether or not we are sliding towards the brink of atomic warfare, remains to be seen. One thing is certain, until we are cognizant of the the terrain we inhabit – and which inhabits us – we are lost at sea.

Text by Nadim Samman