Exhibition: Weight of Shadows – Prix Marcel Duchamp 2021, Centre Pompidou

The sky grows heavy, thickened by the excess carbon dioxide that has been injected into the air since the Industrial Revolution. Its invisible weight—looming over us like a leaden shadow—is the starting point of Julian Charrière’s work. How not merely to represent an environment but to unveil the medium that we move through, and which simultaneously moves through us—that is the cosmological question at stake. Charrière’s work addresses the fading of a modern world-vision that sought to free itself from natural constraints and its transformation in the face of an increasingly dense atmosphere. In its place, he negotiates an image of the world that we can no longer traverse as freely or carelessly, slowed by the density of unregulated carbon emissions that surround us.

To wrestle with these issues, Charrière joined the Leister Scientific Expedition around North Greenland 2021 to the polar ice caps, a place where snow blurs the boundary between ground and sky and the horizon vanishes. There he inverted the conventional mining process: rather than extracting huge hunks of minerals from the earth he gathered tiny molecules of carbon dioxide from the air. He expanded his collection by including the CO2-rich exhalations of people from across the world—a global breath that mirrors and symbolizes the place of the human within global carbon cycle.

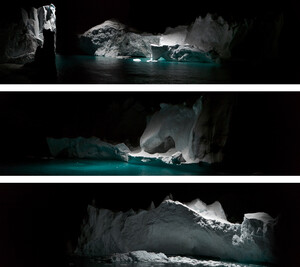

Charrière’s cache of CO2 was then digested by archaea—microorganisms from the depths of the Earth that metabolize the CO2 into methane—before being vaporized in seemingly miraculous fashion into diamonds. Air, synonymous with lightness and softness, is thus alchemically transformed into the hardest naturally-occurring mineral on the planet. Rather than keeping the diamonds, symbolic of wealth and precious excess, Charrière returns them to the polar ice cap, tossing them into a deep well drilled by flowing meltwater. With this gesture, Charriere adds another mineral layer to the open-air archive of successive deposits of atmospheric particles, which over time have formed the ice shield. In adding these shiny fragments to the strata, the artist engages with the paradox of the polar ice caps: they are silent oracles, far from “civilization,” yet they’ve been groaning, creaking, melting—crying out for decades without being heard.

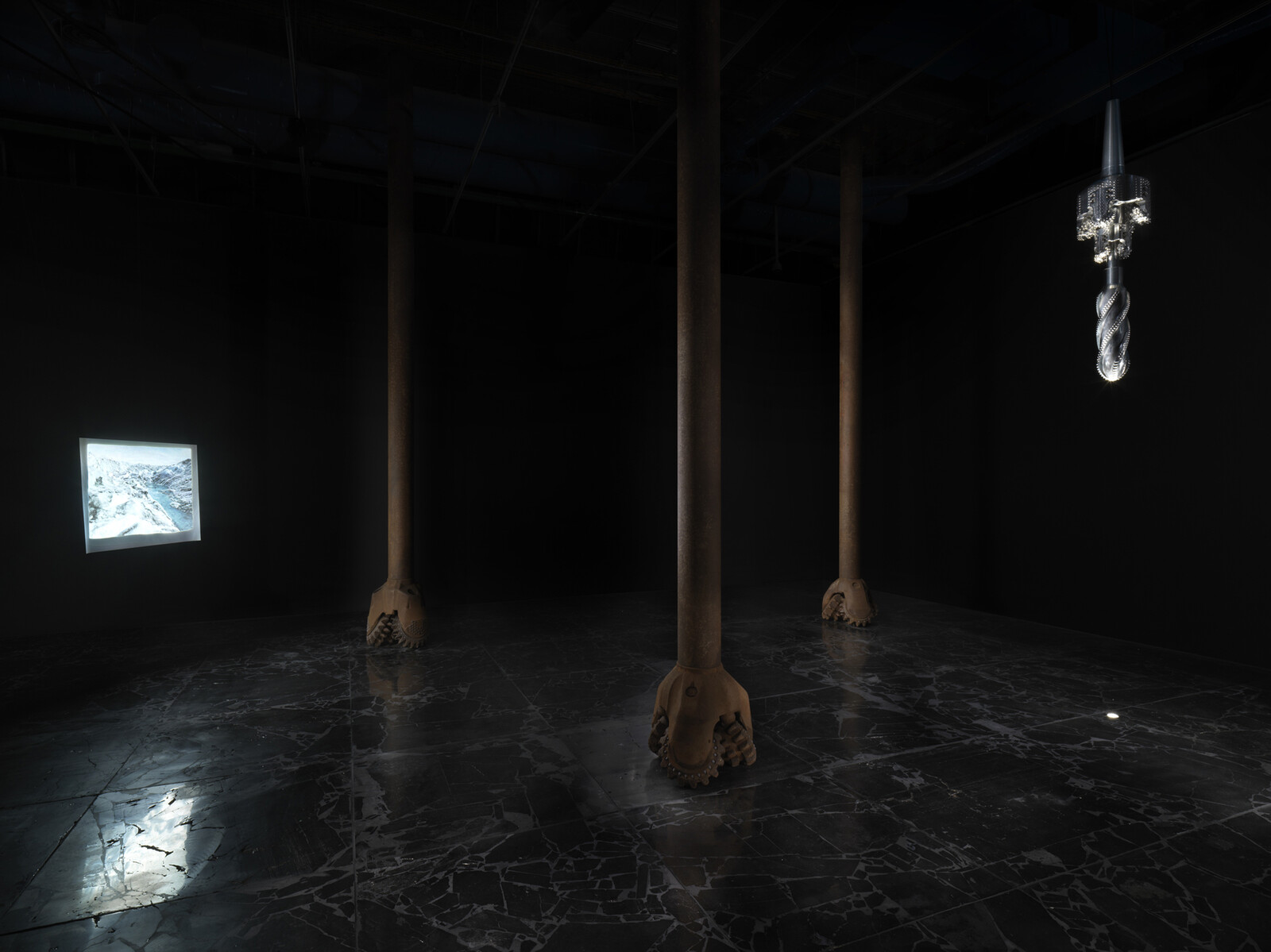

Thus the installation is silent. The floor, a black mirror of polished coal, reflects the ceiling above, emphasizing the intercourse between ground and sky. Oil well drills and their bits, which have penetrated earth’s surface and passed through geological strata and time, stand in the room like ancient columns. One hangs above us, swordlike, its drillbit tipped with the sky diamonds that Charrière has created. And yet the installation is neither temple nor mortuary, but rather a floating space that amplifies the disorientation of the human position not simply on Earth, but also beneath the sky and in an atmosphere.

Charrière’s desire to understand the world as an interconnected organism, in which what exists above us and beneath us is expressed in the surfaces we see and interact with, echoes the work of the great 19th-century naturalists such as Alexander Von Humboldt. Von Humboldt traveled the world widely in order to study the ecological system in its totality: the flora down to their roots, the diversity of the fauna, the chemical composition of the air, the pull of gravity, the power of vulcanism, the blueness of the sky. His naturalistic studies hold powerful empirical and aesthetic importance.

Parallels can be found in Charrière’s project, which does not engage in the heroic gestures, of the lone artist railing at the immensity and indifference of the world, but rather positions the artist as part of a scientific collective, with a specific preoccupation in mind: “an increased belief in science cannot be achieved without a cultural parallel: there is a need for an art which helps to give sense to facts.” (Julian Charrière, 2021)

Text by Martin Guinard

Bibliography

V. Bunkse, Edmunds. 1981. “Humboldt and an Aesthetic Tradition in Geography.” Geographical Review 71:127–146. JSTOR.

Wulf, Andrea. 2017. The Invention of Nature: Alexander von Humboldt's New World. N.p.: Vintage books, a division of Penguin Random House LLC.